Organizational Identity Formation and Change

Theory and research concerning organizational identity (“who we are as an organization”) is a burgeoning domain within organization study. A great deal of conceptual and empirical work has been accomplished within the last three decades—especially concerning the phenomenon of organizational identity change. More recently, work has been devoted to studying the processes and content associated with identity formation. Given the amount of scholarly work done to date, it is an appropriate time to reflect on the perspectives, controversies and outcomes of this body of work. Because organizational identity change has received the preponderance of attention, we first review that extensive literature. We consider the conceptual and empirical work concerning the three putative “pillars” of identity (i.e. that which is ostensibly central, enduring, and distinctive). We devote particular attention to the most controversial of these pillars—the debate pitting a view that sees identity as stable over time (a position we term as the “enduring identity proposition”) and a contrasting stance that sees identity as more changeable (the “dynamic identity proposition”). Following our review of the identity change literature, we next take up a review of the notably smaller compendium of work on identity formation. We consider the conceptual and empirical work devoted to studying the external influences on, as well as the internal resources used, to fashion a nascent identity. Finally, we discuss in more depth the controversies associated with the pillars of identity, assess the four prevalent views on organizational identity (the social construction, social actor, institutionalist, and population ecologist views), assimilate the research on both identity formation and change, and consider the prospects for future work on both phenomena.

High Performance Organization Structures and Characteristics

The search for an ideal or perfect structure is about as futile as trying to find the ideal canned improvement process to drop on the organization (or ourselves). It depends on the organization’s context and focus (vision, values, and purpose), goals and priorities, skill and experience levels, culture, teams’ effectiveness and so on. Each is unique to any organization.

Research and experience shows that the shape and characteristics of high performing organization structures have a number of common features:

Intense Customer and Market Focus — systems, structures, processes, and innovations are all aimed at and flow from the voices of the market and customers. Field people and hands-on senior managers drive the organization in daily contact with customers and partners.

Team-based — operational and improvement teams are used up, down, and across the organization. A multitude of operational teams manage whole systems or self-contained sub-systems such as regions, branches, processes, and complete business units.

Highly Autonomous and Decentralized — dozens, hundreds, or thousands of mini-business units or businesses are created throughout a single company. Local teams adjust their company’s product and service mix to suit their market and conditions. They also reconfigure the existing products and services or develop new experimental prototypes to meet customer/partner needs.

Servant-Leadership — senior managers provide strong Context and Focus (vision, values, and purpose) and strategic direction to guide and shape the organization. Very lean and keen head office management and staff serve the needs of those people doing the work that the customers actually care about and are willing to pay for. Support systems are designed to serve the servers and producers, not management and the bureaucracy.

Networks, Partnerships, and Alliances — organizational and departmental boundaries blur as teams reach out, in, or across to get the expertise, materials, capital, or other support they need to meet customer needs and develop new markets. Learning how to partner with other teams or organizations is fast becoming a critical performance skill.

Fewer and More Focused Staff Professionals — accountants, human resource professionals, improvement specialists, purchasing managers, engineers and designers, and the like, are either in the midst of operational action as a member of an operational team, or they sell their services to a number of teams. Many teams are also purchasing some of this expertise from outside as needed.

Few Management Levels — spans of control stretch into dozens and even hundreds of people (organized in self-managing teams) to one manager. Effective managers are highly skilled in leading (Context and Focus), directing (establishing goals and priorities), and developing (training and coaching).

One Customer Contact Point — although teams and team members will come and go as needed, continuity with the customer is maintained by an unchanging small group or individual. Internal service and support systems serve the needs of the person or team coordinating and managing the customer relationship.

We are in the midst of a major transition from organization and management practices that began around the turn of the 20th century. Our cloudy crystal ball won’t allow us to see which organization structure or model will dominate the 21st century. Since we’re no longer in an age of mass production and standardization, there won’t likely be just one type. Rather, we’ll see our top organizations grow and shed a variety of structures and models to suit the their changing circumstances.

Adapting Organizational Structure to Global Cultures

Organizational structure determines how a business configures its operating units and how they interact to meet business needs. Organizations can be structured in different ways depending on their objectives. But in today’s business environment, where organizations are operating globally and information technologies are changing so quickly, new trends in organizational structure are seemingly evolving as fast as they can be identified. So for those enterprises operating in multiple geographies, it is vital to assess how the diverse cultures of the regions in which they do business affect their organizational structure.

Top Global Trends in Organizational Structure

According to Deloitte global survey of human capital trends, because of “years of struggling to drive employee engagement and retention, improve leadership, and build a meaningful culture, executives see a need to redesign the organization itself, with 92 percent of survey participants rating this as a critical priority. The report goes on to conclude that, “companies are decentralizing authority, moving toward product- and customer-centric organizations, and forming dynamic networks of highly empowered teams that communicate and coordinate activities in unique and powerful ways.”

CEOs and CHROs should, therefore, be working together to understand and create a shared culture, build new management models, design highly empowered teams and develop new leadership and career development models for younger and more globally diverse leaders, employing a strategy of diversity and inclusion.

Why Understanding Values and Culture is Important

As organizations expand into different global regions and move resources abroad, CHROs should be thinking about altering their organizational structure and human resource practices to suit the needs of the region. Although, it is challenging for global organizations to establish and maintain a unified corporate culture and code of conduct when operating in multiple national and regional cultures, leaders should attempt to strike an appropriate balance and allow for the influences of local cultures.

According to the Chartered Quality Institute (CQI), “culture has a strong influence on people’s behavior but is not easily changed. It is an invisible force that consists of deeply held beliefs, values and assumptions that are so ingrained in the fabric of the organization that many people might not be conscious that they hold them.” Executive search firm Spencer Stuart also advises that as organizations grow, they may have to change their organizational structures and reevaluate how they balance global leadership with regional leadership models.

Having executives report to both global and local leadership in a matrix structure that promotes collaboration may provide a broader perspective and help to drive a more customer-centric organizational culture.

Recruiting and Developing Global Employees

For new organizational structures to be effective in rapidly changing environments, ideal employees will be skilled in strategy and management, including new types of people skills. But it can be challenging to recruit and develop talent with the necessary capabilities.

HR leadership should develop programs and processes to educate employees so that they understand what different cultures value, including customs, philosophies and religions. Those values affect how employees behave and interact with each other and with their managers. There should also be a focus on the different workplace practices and behaviors, including varying reward systems, employee development and oversight, and employees should be prepared for common workplace situations, such as how people communicate (verbally and nonverbally), interact with others, make decisions, complete tasks, negotiate and deal with conflict.

In global organizations, managers are faced with leading international teams, often virtually. They may need to negotiate with vendors and suppliers abroad, as well. All of these situations require different types of knowledge and skills if employees are to succeed in working with new people, bridging cultural gaps and achieving business objectives.

Spencer Stuart suggests recruiting local talent and giving people cross-geographical and cross-functional assignments as ways to develop employees to assume complex international roles.

The 5 Classic Mistakes in Organizational Structure: Or, How to Design Your Organization the Right Way

If I were to ask you a random and seemingly strange question, “Why does a rocket behave the way it does and how is it different from a parachute that behaves the way it does?” You’d probably say something like, “Well, duh, they’re designed differently. One is designed to go fast and far and the other is designed to cause drag and slow an objection in motion. Because they’re designed differently, they behave differently.” And you’d be correct. How something is designed controls how it behaves. (If you doubt this, just try attaching an engine directly to a parachute and see what happens).

But if I were to ask you a similar question about your business, “Why does your business behave the way it does and how can you make it behave differently?” would you answer “design?” Very few people — even management experts — would. But the fact is that how your organization is designed determines how it performs. If you want to improve organizational performance, you’ll need to change the organizational design. And the heart of organizational design is its structure.

Form Follows Function — The 3 Elements of Organizational Structure & Design

There’s a saying in architecture and design that “form follows function.” Put another way, the design of something should support its purpose. For example, take a minute and observe the environment you’re sitting in (the room, building, vehicle, etc.) as well as the objects in it (the computer, phone, chair, books, coffee mug, and so on). Notice how everything serves a particular purpose. The purpose of a chair is to support a sitting human being, which is why it’s designed the way it is. Great design means that something is structured in such a way that it allows it to serve its purpose very well. All of its parts are of the right type and placed exactly where they should be for their intended purpose. Poor design is just the opposite. Like a chair with an uncomfortable seat or an oddly measured leg, a poorly designed object just doesn’t perform like you want it to.

Even though your organization is a complex adaptive system and not static object, the same principles hold true. If the organization has a flawed design, it simply won’t perform well. It must be structured (or restructured) to create an design that supports its function or business strategy. Just like a chair, all of its parts or functions must be of the right type and placed in the right location so that the entire system works well together. What actually gives an organization its “shape” and controls how it performs are three things:

- The functions it performs.

- The location of each function.

- The authority of each function within its domain.

The functions an organization performs are the core areas or activities it must engage in to accomplish its strategy (e.g. sales, customer service, marketing, accounting, finance, operations, CEO, admin, HR, legal, PR, R&D, engineering, etc.). The location of each function is where it is placed in the organizational structure and how it interacts with other functions. The authority of a function refers to its ability to make decisions within its domain and to perform its activities without unnecessary encumbrance. A sound organizational structure will make it unarguably clear what each function (and ultimately each person) is accountable for. In addition, the design must both support the current business strategy and allow the organization to adapt to changing market conditions and customer needs over time.

What Happens When an Organization’s Structure Gets Misaligned?

When you know what to look for, it’s pretty easy to identify when an organization’s structure is out of whack. Imagine a company with an existing cash cow business that is coming under severe pricing pressure. Its margins are deteriorating quickly and the market is changing rapidly. Everyone in the company knows that it must adapt or die. Its chosen strategy is to continue to milk the cash cow (while it can) and use those proceeds to invest in new verticals. On paper, it realigns some reporting functions and allocates more budget to new business development units. It holds an all-hands meeting to talk about the new strategy and the future of the business. Confidence is high. The team is a good one. Everyone is genuinely committed to the new strategy. They launch with gusto.

But here’s the catch. Beneath the surface-level changes, the old power structures remain. This is a common problem with companies at this stage. The “new” structure is really just added to the old one, like a house with an addition – and things get confusing. Who’s responsible for which part of the house? While employees genuinely want the new business units to thrive, there’s often a lack of clarity, authority, and accountability around them. In addition, the new business units, which need freedom to operate in startup mode, have to deal with an existing bureaucracy and old ways of doing things. The CEO is generally oblivious to these problems until late in the game. Everyone continues to pay lip service to the strategy and the importance of the new business units but doubt, frustration, and a feeling of ineptitude have already crept in. How this happens will become clearer as you read on.

Edwards Demming astutely recognized that “a bad system will defeat a good person every time.” The same is true of organizational structure. Structure dictates the relationship of authority and accountability in an organization and, therefore, also how people function. For this reason, a good team can only be as effective as the structure supporting it. For even the best of us, it can be very challenging to operate within an outdated or dysfunctional structure. It’s like trying to sail a ship with a misaligned tiller. The wind is in your sails, you know the direction you want to take, but the boat keeps fighting against itself.

An organization’s structure gets misaligned for many reasons. But the most common one is simply inertia. The company gets stuck in an old way of doing things and has trouble breaking free of the past. How did it get this way to begin with? When an organization is in startup to early growth mode, the founder(s) control most of the core functions. The founding engineer is also the head of sales, finance, and customer service. As the business grows, the founder(s) become a bottleneck to growth — they simply can’t do it all at a larger scale. So they make key hires to replace themselves in selected functions – for example, a technical founder hires a head of sales and delegates authority to find, sell, and close new accounts. At the same time, the founder(s) usually find it challenging to determine how much authority to give up (too much and the business could get ruined; too little and they’ll get burned out trying to manage it all).

As the business and surrounding context develop over time, people settle into their roles and ways of operating. The structure seems to happen organically. From an outsider’s perspective, it may be hard to figure out how and why the company looks and acts the way it does. And yet, from the inside, we grow used to things over time and question them less: “It’s just how we do things around here.” Organizations continue to operate, business as usual, until a new opportunity or a market crisis strikes and they realize they can’t succeed with their current structures.

What are the signs that a current structure isn’t working? You’ll know its time to change the structure when inertia seems to dominate — in other words, the strategy and opportunity seem clear, people have bought in, and yet the company can’t achieve escape velocity. Perhaps it’s repeating the same execution mistakes or making new hires that repeatedly fail (often a sign of structural imbalance rather than bad hiring decisions). There may be confusion among functions and roles, decision-making bottlenecks within the power centers, or simply slow execution all around. If any of these things are happening, it’s time to do the hard but rewarding work of creating a new structure.

The 5 Classic Mistakes in Organizational Structure

Here are five telltale signs of structure done wrong. As you read them, see if your organization has made any of these mistakes. If so, it’s a sure sign that your current structure is having a negative impact on performance.

Mistake #1: The strategy changes but the structure does not

Every time the strategy changes — including when there’s a shift to a new stage of the execution lifecycle — you’ll need to re-evaluate and change to the structure. The classic mistake made in restructuring is that the new form of the organization follows the old one to a large degree. That is, a new strategy is created but the old hierarchy remains embedded in the so-called “new” structure. Instead, you need to make a clean break with the past and design the new structure with a fresh eye. Does that sound difficult? It generally does. The fact is that changing structure in a business can seem really daunting because of all the past precedents that exist – interpersonal relationships, expectations, roles, career trajectories, and functions. And in general, people will fight any change that results in a real or perceived loss of power. All of these things can make it difficult to make a clean break from the past and take a fresh look at what the business should be now. There’s an old adage that you can’t see the picture when you’re standing in it. It’s true. When it comes to restructuring, you need to make a clean break from the status quo and help your staff look at things with fresh eyes. For this reason, restructuring done wrong will exacerbate attachment to the status quo and natural resistance to change. Restructuring done right, on the other hand, will address and release resistance to structural change, helping those affected to see the full picture, as well as to understand and appreciate their new roles in it.

Mistake #2: Functions focused on effectiveness report to functions focused on efficiency

Efficiency will always tend to overpower effectiveness. Because of this, you’ll never want to have functions focused on effectiveness (sales, marketing, people development, account management, and strategy) reporting to functions focused on efficiency (operations, quality control, administration, and customer service). For example, imagine a company predominantly focused on achieving Six Sigma efficiency (which is doing things “right”). Over time, the processes and systems become so efficient and tightly controlled, that there is very little flexibility or margin for error. By its nature, effectiveness (which is doing the right thing), which includes innovation and adapting to change, requires flexibility and margin for error. Keep in mind, therefore, that things can become so efficient that they lose their effectiveness. The takeaway here is: always avoid having functions focused on effectiveness reporting to functions focused on efficiency. If you do, your company will lose its effectiveness over time and it will fail.

Mistake #3: Functions focused on long-range development report to functions focused on short-range results

Just as efficiency overpowers effectiveness, the demands of today always overpower the needs of tomorrow. That’s why the pressure you feel to do the daily work keeps you from spending as much time with your family as you want to. It’s why the pressure to hit this quarter’s numbers makes it so hard to maintain your exercise regime. And it’s why you never want to have functions that are focused on long-range development (branding, strategy, R&D, people development, etc.) reporting to functions focused on driving daily results (sales, running current marketing campaigns, administration, operations, etc.). For example, what happens if the marketing strategy function (a long-range orientation focused on branding, positioning, strategy, etc.) reports into the sales function (a short-range orientation focused on executing results now)? It’s easy to see that the marketing strategy function will quickly succumb to the pressure of sales and become a sales support function. Sales may get what it thinks it needs in the short run but the company will totally lose its ability to develop its products, brands, and strategy over the long range as a result.

Mistake #4: Not balancing the need for autonomy vs. the need for control

The autonomy to sell and meet customer needs should always take precedence in the structure — for without sales and repeat sales the organization will quickly cease to exist. At the same time, the organization must exercise certain controls to protect itself from systemic harm (the kind of harm that can destroy the entire organization). Notice that there is an inherent and natural conflict between autonomy and control. One needs freedom to produce results, the other needs to regulate for greater efficiencies. The design principle here is that as much autonomy as possible should be given to those closest to the customer (functions like sales and account management) while the ability to control for systemic risk (functions like accounting, legal, and HR) should be as centralized as possible. Basically, rather than trying to make these functions play nice together, this design principle recognizes that inherent conflict, plans for it, and creates a structure that attempts to harness it for the overall good of the organization. For example, if Sales is forced to follow a bunch of bureaucratic accounting and legal procedures to win a new account, sales will suffer. However, if the sales team sells a bunch of underqualified leads that can’t pay, the whole company suffers. Therefore, Sales should be able to sell without restriction but also bear the burden of underperforming accounts. At the same time, Accounting and Legal should be centralized because if there’s a loss of cash or a legal liability, the whole business is at risk. So the structure must call this inherent conflict out and make it constructive for the entire business.

Mistake #5: Having the wrong people in the right functions

I’m going to talk about how to avoid this mistake in greater detail in a coming article in this series but the basics are simple to grasp. Your structure is only as good as the people operating within it and how well they’re matched to their jobs. Every function has a group of activities it must perform. At their core, these activities can be understood as expressing PSIU requirements. Every person has a natural style. It’s self-evident that when there’s close alignment between job requirements and an individual’s style and experience, and assuming they’re a #1 Team Leader in the Vision and Values matrix, then they’ll perform at a high level. In the race for market share, however, companies make the mistake of mis-fitting styles to functions because of perceived time and resource constraints. For example, imagine a company that just lost its VP of Sales who is a PsIu (Producer/Innovator) style. They also have an existing top-notch account manager who has a pSiU (Stabilizer/Unifier) style. Because management believes they can’t afford to take the time and risk of hiring a new VP of Sales, they move the Account Manager into the VP of Sales role and give him a commission-based sales plan in the hope that this will incentivize him to perform as a sales person. Will the Account Manager be successful? No. It’s not in his nature to hunt new sales. It’s his nature to harvest accounts, follow a process, and help customers feel happy with their experience. As a result, sales will suffer and the Account Manager, once happy in his job, is now suffering too. While we all have to play the hand we’re dealt with, placing people in misaligned roles is always a recipe for failure. If you have to play this card, make it clear to everyone that it’s only for the short run and the top priority is to find a candidate who is the right fit as soon as possible.

How to Design Your Organization’s Structure

The first step in designing the new structure is to identify the core functions that must be performed in support of the business strategy, what each function will have authority and be accountable for, and how each function will be measured (Key Performance Indicators or KPIs). Then, avoiding the 5 classic mistakes of structure above, place those functions in the right locations within the organizational structure. Once this is completed, the structure acts as a blueprint for an organizational chart that calls out individual roles and (hats). A role is the primary task that an individual performs. A (hat) is a secondary role that an individual performs. Every individual in the organization should have one primary role and — depending on the size, complexity, and resources of the business — may wear multiple (hats). For example, a startup founder plays the CEO role and also wears the hats of (Business Development) and (Finance). As the company grows and acquires more resources, she will give up hats to new hires in order to better focus on her core role.

Getting an individual to gracefully let go of a role or a hat that has outgrown them can be challenging. They may think and feel, “I’m not giving up my job! I’ve worked here for five years and now I have to report to this Johnny-Come-Lately?” That’s a refrain that every growth-oriented company must deal with at some point. One thing that can help this transition is to focus not on the job titles but on the PSIU requirements of each function. Then help the individual to identify the characteristics of the job that they’re really good at and that they really enjoy and seek alignment with a job that has those requirements. For example, the title VP of Sales is impressive. But if you break it down into its core PSIU requirements, you’ll see that it’s really about cold calling, managing a team, and hitting a quota (PSiU). With such a change in perspective, the current Director of Sales who is being asked to make a change may realize, “Hmm… I actually HATE cold calling and managing a team of reps. I’d much rather manage accounts that we’ve already closed and treat them great. I’m happy to give this up.” Again, navigating these complex emotional issues is hard and can cost the company a lot of energy. This is one of the many reasons that using a sound organizational restructuring process is essential.

A structural diagram may look similar to an org chart but there are some important differences. An org chart shows the reporting functions between people. What we’re concerned with here, first and foremost, are the functions that need to be performed by the business and where authority will reside in the structure. The goal is to first design the structure to support the strategy (without including individual names) and then to align the right people within that structure. Consequently, an org chart should follow the structure, not the other way around. This will help everyone avoid the trap of past precedents that I discussed earlier. This means – literally – taking any individual name off the paper until the structure is designed correctly. Once this is accomplished, individual names are added into roles and (hats) within the structure.

After restructuring, the CEO works with each new functional head to roll out budgets, targets, and rewards for their departments. The most important aspect of bringing a structure to life, however, isn’t the structure itself, but rather the process of decision making and implementation that goes along with it. The goal is not to create islands or fiefdoms but an integrated organization where all of the parts work well together. If structure is the bones or shape of an organization, then the process of decision making and implementation is the heart of it. I’m going to discuss this process in greater detail in the next article in this series. It can take a few weeks to a few months to get the structure humming and people comfortable in their new roles. You’ll know you’ve done it right when the structure fades to the background again and becomes almost invisible. It’s ironic that you do the hard work of restructuring so you can forget about structure. Post integration, people should be once again clear on their roles, hats, and accountabilities. The organization starts to really hum in its performance and execution speed picks up noticeably. Roaring down the tracks towards a common objective is one of the best feelings in business. A good structure makes it possible.

Structure Done Wrong: An Example to Avoid

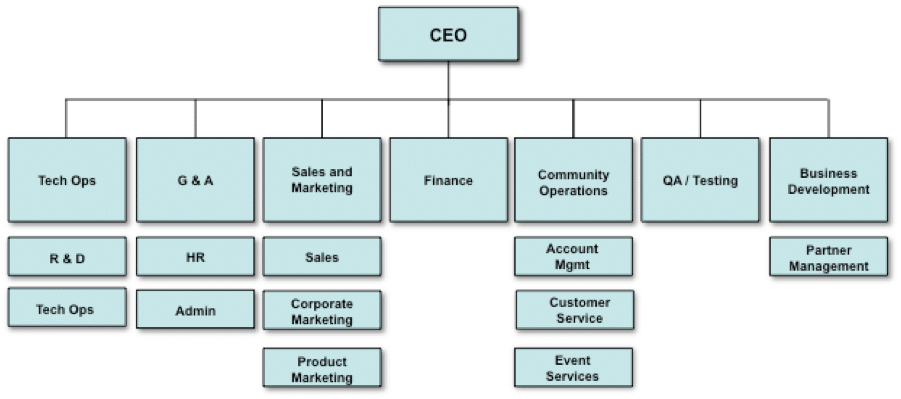

Below is a picture of a typical business structure done wrong. The company is a software as a service (Saas) provider that has developed a new virtual trade show platform. They have about ten staff and $2M in annual revenues. I received this proposed structure just as the company was raising capital and hiring staff to scale its business and attack multiple industry verticals at once. In addition to securing growth capital, the company’s greatest challenge is shifting from a startup where the two co-founders do most everything to a scalable company where the co-founders can focus on what they do best.

So what’s wrong with this structure? Several things. First, this proposed structure was created based on the past precedents within the company, not the core functions that need to be performed in order to execute the new strategy. This will make for fuzzy accountability, an inability to scale easily, new hires struggling to make a difference and navigate the organization, and the existing team having a hard time growing out of their former hats into dedicated roles. It’s difficult to tell what are the key staff the company should hire and in what sequence. It’s more likely that current staff will inherit functions that they’ve always done, or that no one else has been trained to do. If this structure is adopted, the company will plod along, entropy and internal friction will rise, and the company will fail to scale.

The second issue with the proposed structure is that efficiency functions (Tech Ops and Community Operations) are given authority over effectiveness functions (R&D and Account Management). What will happen in this case? The company’s operations will become very efficient but will lose effectiveness. Imagine being in charge of R&D, which requires exploration and risk taking, but having to report every day to Tech Ops, which requires great control and risk mitigation. R&D will never flourish in this environment. Or imagine being in charge of the company’s key accounts as the Account Manager. To be effective, you must give these key accounts extra care and attention. But within this structure there’s an increasing demand to standardize towards greater efficiency because that’s what Community Operations requires. Efficiency always trumps effectiveness over time and therefore, the company will lose its effectiveness within this structure.

Third, short-run functions are given authority over long-run needs. For example, Sales & Marketing are both focused on effectiveness but should rarely, if ever, be the same function. Sales has a short-run focus, marketing a long-run focus. If Marketing reports to Sales, then Marketing will begin to look like a sales support function, instead of a long-run positioning, strategy, and differentiation function. As market needs shift, the company’s marketing effectiveness will lose step and focus. It won’t be able to meet the long-run needs for the company.

Fourth, it’s impossible to distinguish where the authority to meet customer needs resides and how the company is controlling for systemic risk. As you look again at the proposed structure, how does the company scale? Where is new staff added and why? What’s the right sequence to add them? Who is ultimately responsible for profit and loss? Certainly it’s the CEO but if the CEO is running the day-to-day P&L across multiple verticals, then he is not going to be able to focus on the big picture and overall execution. At the same time, who is responsible for mitigating systemic risk? Within this current structure, it’s very likely that the CEO never extracts himself from those activities he’s always done and shouldn’t still be doing if the business is to scale. If he does attempt to extract himself, he’ll delegate without the requisite controls in place and the company will make a major mistake that threatens its life.

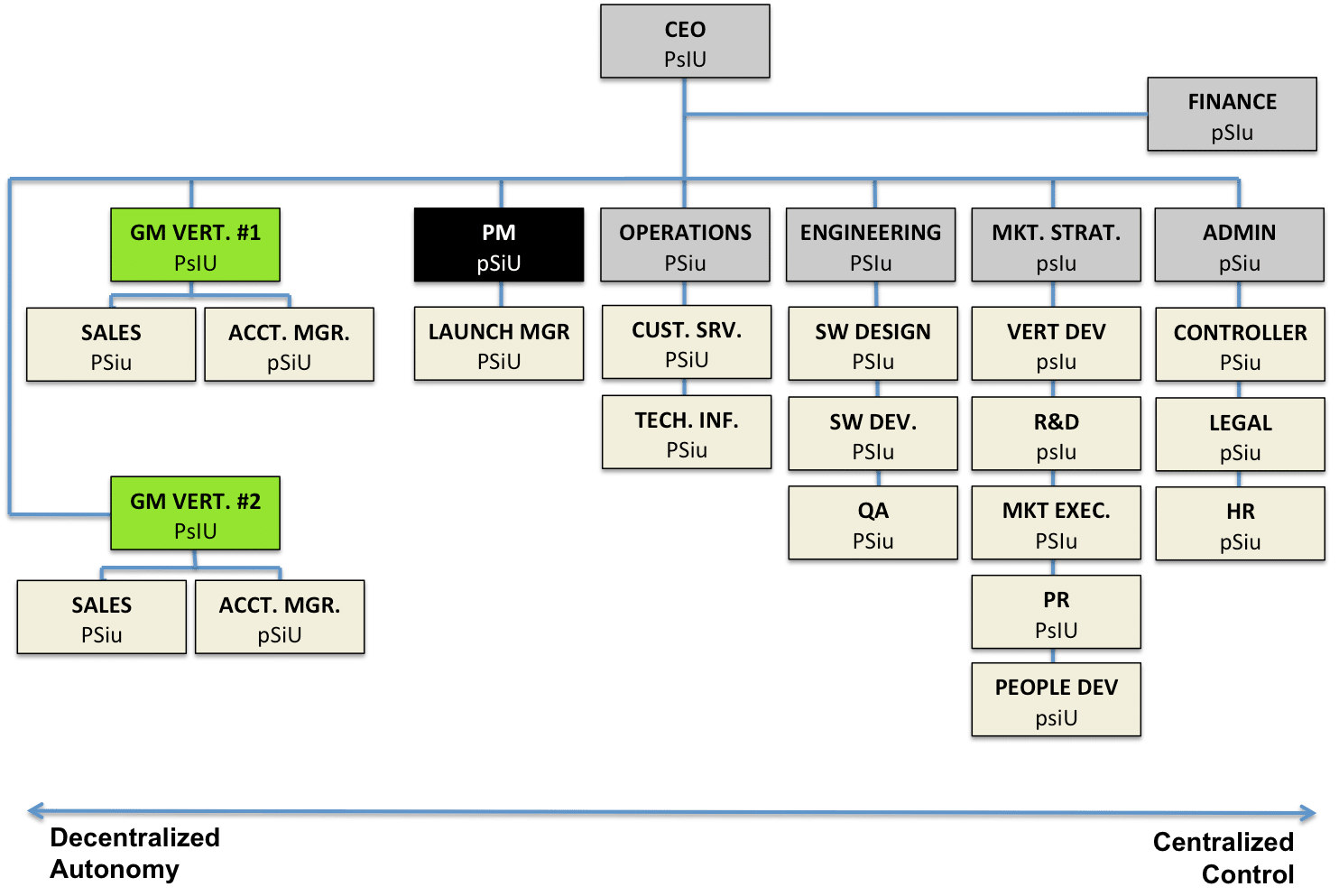

Structure Done Right

Below is a picture of how I realigned the company’s structure to match its desired strategy. Here are some of the key things to recognize about this new structure and why it’s superior to the old one. Each box represents a key function that must be performed by the business in its chosen strategy. Again, this is not an org chart. One function may have multiple people such as three customer service reps within it and certain staff may be wearing multiple different hats. So when creating the structure, ignore the people involved and just identify the core business functions that must be performed. Again, first we want to create the right structure to support the chosen strategy. Then we can add roles and hats.

How to Read this Structure

At the bottom of the structure you’ll see an arrow with “decentralized autonomy” on the left and “centralized control” on the right. That is, your goal is to push decision-making and autonomy out as far as possible to the left of the structure for those functions closest to the customer. At the same time you need to control for systemic risk on the right of the structure for those functions closest to the enterprise. There is a natural conflict that exists between decentralized autonomy and centralized control. This structure recognizes that conflict, plans for it, and creates a design that will harness and make it constructive. Here’s how.

Within each function, you’ll see a label that describes what it does, such as CEO, Sales, or Engineering. These descriptions are not work titles for people but basic definitions of what each function does. Next to each description is its primary set of PSIU forces. PSIU is like a management shorthand that describes the forces of each function. For example, the CEO function needs to produce results, innovate for changing demands, and keep the team unified: PsIU.

Identifying the PSIU code for each function is helpful for two reasons. One, it allows a shared understanding of what’s really required to perform a function. Two, when it’s time to place people into hats and roles within those functions, it enables you to find a match between an individual’s management style and the requirements for the role that needs to be performed. For example, the Account Management function needs to follow a process and display a great aptitude towards interaction with people (pSiU). Intuitively you already know that you’d want to fill that role with a person who naturally expresses a pSiU style. As I mentioned earlier, it would be a mistake to take a pSiU Account Manager and place them into a Sales role that requires PSiu, give them a commission plan, and expect them to be successful. It’s against their very nature to be high-driving and high-charging and no commission plan is going to change that. It’s always superior to match an individual’s style to a role rather than the other way around. Now that you understand the basics of this structure, let’s dive into the major functions so you can see why I designed it the way I did.

The General Manager (GM) Function

The first and most important thing to recognize is that, with this new structure, it’s now clear how to scale the business. The green boxes “GM Vertical #1 and #2” on the far left of the structure are called business units. The business units represent where revenues will flow to the organization. They’re colored green because that’s where the money flows. The GM role is created either as a dedicated role or in the interim as a (hat) worn by the CEO until a dedicated role can be hired. Each business unit recognizes revenue from the clients within their respective vertical. How the verticals are segmented will be determined by business and market needs and the strategy. For example, one GM may have authority for North America and the other Asia/Pacific. Or one might have authority for the entertainment industry and the other the finance industry. Whatever verticals are chosen, the structure identifies authority and responsibility for them. Notice that the code for the GM/PsIU is identical to the CEO/PsIU. This is because the GMs are effectively CEOs of their own business units or can be thought of as future CEOs in training for the entire organization.

Underneath each green business unit is a Sales role, responsible for selling new accounts and an Account Management role, responsible for satisfying the needs of key clients. Essentially, by pushing the revenue driving functions to the far left of the structure, we are able to decentralize autonomy by giving each GM the authority and responsibility to drive revenue, acquire new customers, meet the needs of those customers. Each GM will have targets for revenue, number of customers, and client satisfaction. They also have a budget and bonus structure.

The Product Manager (PM) Function

To the immediate right of the green business units is a black box called “PM” or Product Manager. The function of the Product Manager is to manage the competing demands of the different verticals (the green boxes to its left) as well as the competing demands of the other business functions (the grey boxes to its right) while ensuring high product quality and market fit and driving a profit. The grey boxes to the right of the Product Manager — CEO, Finance, Operations, Engineering, Marketing Strategy, and Admin — represent the rest of the core organizational functions. Effectively, these functions provide services to the green business units so that those units have products to sell to their markets. The revenue that the business generates pays for those internal services. Profits are derived by subtracting the cost of those services from the revenues generated by the business units. A Launch Manager who helps to coordinate new product releases between the business units supports the Product Manager.

The code for the Product Manager is pSiU. That is, we need the Product Manager to be able to stabilize and unify all of the competing demands from the organization. What kind of competing demands? The list is almost endless. First, there will be competing demands from the verticals. One vertical will want widget X because it meets the needs of their customers; the other will want widget Z for the same reasons (and remember that this particular company’s strategy is to run multiple verticals off a single horizontal platform). Operations will want a stable product that doesn’t crash and integrates well within the existing infrastructure. Engineering will want a cutting-edge product that displays the latest functions. Marketing Strategy will want a product that matches the company’s long-range plans. Administration will want a product that doesn’t cause the company to get sued. The CEO will want a product that tells a great story to the marketplace. Finance will want a product that generates significant ROI or one that doesn’t require a lot of investment, depending on its lifecycle stage. So the list of inherent conflicts runs deep.

The reason we don’t want a psIu in the Product Manager is that at this stage of the company’s lifecycle, the innovative force is very strong within the founding team, which will continue to provide that vision and innovation in another role, new Vertical Development and R&D under Marketing Strategy (more on this later). Nor do we want a Psiu in the Product Manager function because a big producer will focus on driving forward quickly and relentlessly (essential in the earlier stages of the product lifecycle) but will miss many of the details and planning involved with a professional product release (essential at this stage of the product lifecycle).

It’s worth discussing why we want the product P&L to accrue to the Product Manager function and not the CEO or GMs. By using this structure, the CEO delegates autonomy to the GMs to drive revenue for their respective verticals and for the Product Manager to drive profits across all verticals. Why not give P&L responsibility to the CEO? Of course the ultimate P&L will roll up to the CEO but it’s first recognized and allocated to the Product Manager. This allows the CEO to delegate responsibility for product execution in the short run while also balancing the long-range needs of the product and strategy.

We don’t give the Product Manager function to the GMs at this stage for a different reason. If we did, the product would have an extreme short-run focus and wouldn’t account for long-run needs. The business couldn’t adapt for change and it would miss new market opportunities. However, the GMs will need to have significant input into the product features and functions. That’s why the Product Manager is placed next to the GMs and given quite a lot of autonomy – if the product isn’t producing results in the short run for the GMs, it’s not going to be around in the long run. At the same time, the product must also balance and prioritize long-range needs and strategy and that’s why it doesn’t report to the GMs directly.

If the business continues to grow, then one of the GMs will become the head of an entire division. Think of a division as a grouping of multiple similar verticals. In this case, the Product Manager function may in fact be placed under the newly formed division head because it is now its own unique business with enough stability and growth to warrant that level of autonomy. Remember that structures aren’t stagnant and they must change at each new stage of the lifecycle or each change in strategy. For this current stage of the lifecycle, creating a dynamic tension between the GMs, the Product Manager, and the rest of the organization is highly desired because it will help to ensure a sound product/market/execution fit. I’ll explain more of how this tension plays out and how to harness it for good decision making in the next article.

The Operations Function

To the immediate right of the Product Manager is Operations. This is the common services architecture that all GMs use to run their business. It is designed for scalable efficiency and includes such functions as Customer Service and Technology Infrastructure. Notice how all of these functions are geared towards short-run efficiency, while the business still wants to encourage short-term effectiveness (getting new clients quickly, adapting to changing requests from the GMs, etc.) within these roles and so it gives more autonomy to this unit than to those to the right of it. The code for Operations is PSiU because we need it to produce results for clients every day (P); it must be highly stable and secure (S); and it must maintain a client-centric perspective (U). It’s important to recognize that every function in the business has a client that it serves. In the case of Operations, the clients are both internal (the other business functions) as well as external (the customers).

The Engineering Function

Going from left to right, the next core function is Engineering. Here the core functions of the business include producing effective and efficient architectures and designs that Operations will use to run their operations. This includes SW Design, SW Development, and QA. Notice, however, that the ultimate deployment of new software is controlled by the Product Manager (Launch Manager) and that provides an additional QA check on software from a business (not just a technology) perspective. Similar to Operations, Engineering is also short-run oriented and needs to be both effective and efficient. It is given less relative autonomy in what it produces and how it produces it due to the fact that Engineering must meet the needs of all other business functions, short- and long-run. The code for Engineering is PSIu because we need it to produce results now (P) and to have quality code, architecture, and designs (S), and to be able to help create new innovations (I) in the product.

The Marketing Strategy Function

The next core function is Marketing Strategy. Marketing Strategy is the process of aligning core capabilities with growing opportunities. It creates long-run effectiveness. It’s code is psIu because it’s all about long-term innovation and nurturing and defending the vision. Sub-functions include new Vertical Development (early stage business development for future new verticals that will ultimately be spun out into a GM group), R&D (research and development), Marketing Execution (driving marketing tactics to support the strategy), PR, and People Development. A few of these sub-functions warrant a deeper explanation.

The reason new Vertical or Business Development is placed here is that the act of seeding a new potential vertical requires a tremendous amount of drive, patience, creativity, and innovation. If this function were placed under a GM, then it would be under too much pressure to hit short-run financial targets and the company would sacrifice what could be great long-term potential. Once the development has started and the vertical has early revenue and looks promising, it can be given to a new or existing GM to scale.

The purpose of placing R&D under Marketing Strategy is to allow for the long-run planning and innovative feature development that can be applied across all business units. The short-run product management function is performed by the Product Manager. The Product Manager’s job is to manage the product for the short run while the visionary entrepreneur can still perform R&D for the long run. By keeping the Product Manager function outside of the GM role, New Product Development can more easily influence the product roadmap. Similarly, by keeping the Product Manager function outside of Marketing Strategy, the company doesn’t lose sight of what’s really required in the product today as needed by the GMs. Similarly, if the R&D function was placed under Engineering, it would succumb to the short range time pressure of Engineering and simply become a new feature development program — not true innovative R&D.

The reason Marketing Execution is not placed under the GM is that it would quickly become a sales support function. Clearly, the GM will want to own their own marketing execution and he or she may even fight to get it. It’s the CEO’s role, however, to ensure that Marketing Execution supports the long-range strategy and thus, Marketing Execution should remain under Marketing Strategy.

The basis for placing People Development under Marketing Strategy rather than under HR is that People Development is a long-range effectiveness function. If it’s placed under HR, then it will quickly devolve into a short-range tactical training function. For a similar reason, recruitment is kept here because a good recruiter will thrive under the long-range personal development function and will better reflect the organization’s real culture.

The Finance & Admin Functions

To the far right of the organization are the Administrative functions. Here reside all of the short-run efficiency or Stabilizing functions that, if performed incorrectly, will quickly cause the organization to fail. These functions include collecting cash Controller (AR/AP), Legal, and the HR function of hiring and firing. Notice, however, that the Finance function is not grouped with Admin. There are two types of Finance. One, cash collections and payments, is an Admin function. The other, how to deploy the cash and perform strategic financial operations, is a long-run effectiveness function. If Finance is placed over Admin, or under Admin, the company will either suffer from lack of effectiveness or a lack of efficiency, respectively. It also creates a tremendous liability risk to allow one function to control cash collections and cash deployments. It’s better to separate these functions for better performance and better control.

The CEO Function

The top function is the CEO. Here resides the ultimate authority and the responsibility to keep the organization efficient and effective in the short and long run. The code for the CEO is PsIU because this role requires driving results, innovating for market changes, and keeping the team unified. By using this structure, the CEO delegates autonomy to the GMs to produce results for their respective verticals. The GMs are empowered to produce results and also to face the consequences of not achieving them by “owning” the revenue streams. The CEO has delegated short-run Product Management to produce a profit according to the plan and simultaneously balances short- and long-run product development needs. At the same time, the CEO protects the organization from systemic harm by centralizing and controlling those things that pose a significant liability. So while the GMs can sell, they can’t authorize contracts, hire or fire, or collect cash or make payments without the authorization of the far right of the structure. Nor can they set the strategy, destroy the brand, or cause a disruption in operations without the authority of the CEO and other business units.

The goal of structure is to create clarity of authority and responsibility for the core organizational functions that must be performed and to create a design that harness the natural conflict that exists between efficiency and effectiveness, short-run and long-run, decentralization and control. A good CEO will encourage the natural conflict to arise within the structure and then deal with it in a constructive way. More on how to do this in the next section.

Remember that within any structure, individuals will play a role and, especially in a start-up environment, wear multiple hats. How you fill roles and hats is to first identify and align the core functions to support the organization’s strategy. Then, assign individuals to those functions as either a role or a hat. In this particular structure, the role of CEO was played by one founder who also wore the temporary hats of GM Vertical #1 and #2 until a new GM could be hired. The other founder played the role of Product Manager, as well as Engineer until that role could be hired. Clearly delineating these functions allowed them both to recognize which roles they needed to hire for first so that they could give up the extra hats and focus on their dedicated roles to grow the business. Going forward, both founders will share a hat in Marketing Strategy with one focused on new Business Development and the other on R&D. These Marketing Strategy hats play to the strength of each founder and allow them to maintain the more creative, agile aspects of entrepreneurship while the business structure is in place to execute on the day-to-day strategy.

Summary of Organizational Structure & Design

To recap, design controls behavior. When an organization’s structure is misaligned, its resistance to change will be great and its execution will be slow. Organizational structures get misaligned over time for many reasons. The most basic of these is inertia, through which companies get stuck in old ways of doing things. When restructuring your organization, there are some classic mistakes to avoid. First, always redesign the structure whenever you change the strategy or shift to a new lifecycle stage (do this even if there are no personnel changes). Second, avoid placing efficiency-based functions such as operations or quality control over effectiveness-based functions such as R&D, strategy, and training. Third, avoid giving short-range functions like Sales, Operations, and Engineering power over long-range functions like Marketing, R&D, and People Development. Fourth, distinguish between the need to decentralize autonomy and centralize control and structure the organization accordingly. Finally, avoid placing the wrong style of manager within the new structural role simply because that’s the past precedent. Changing structures can be really hard because there’s so much past precedent. If the organization is going to thrive, however, the new structure must support the new strategy. In the next article, I’m going to discuss the most important process of any business: the decision making and implementation that brings the structure alive.

Different Types of Organizational Structure

Organizations are set up in specific ways to accomplish different goals, and the structure of an organization can help or hinder its progress toward accomplishing these goals. Organizations large and small can achieve higher sales and other profit by properly matching their needs with the structure they use to operate. There are three main types of organizational structure: functional, divisional and matrix structure.

Functional Structure

Functional structure is set up so that each portion of the organization is grouped according to its purpose. In this type of organization, for example, there may be a marketing department, a sales department and a production department. The functional structure works very well for small businesses in which each department can rely on the talent and knowledge of its workers and support itself. However, one of the drawbacks to a functional structure is that the coordination and communication between departments can be restricted by the organizational boundaries of having the various departments working separately.

Divisional Structure

Divisional structure typically is used in larger companies that operate in a wide geographic area or that have separate smaller organizations within the umbrella group to cover different types of products or market areas. For example, the now-defunct Tecumseh Products Company was organized divisionally–with a small engine division, a compressor division, a parts division and divisions for each geographic area to handle specific needs. The benefit of this structure is that needs can be met more rapidly and more specifically; however, communication is inhibited because employees in different divisions are not working together. Divisional structure is costly because of its size and scope. Small businesses can use a divisional structure on a smaller scale, having different offices in different parts of the city, for example, or assigning different sales teams to handle different geographic areas.

Matrix

The third main type of organizational structure, called the matrix structure, is a hybrid of divisional and functional structure. Typically used in large multinational companies, the matrix structure allows for the benefits of functional and divisional structures to exist in one organization. This can create power struggles because most areas of the company will have a dual management–a functional manager and a product or divisional manager working at the same level and covering some of the same managerial territory.

Purpose of Organizational Structure

Organizational structure is about definition and clarity. Think of structure as the skeleton supporting the organization and giving it shape. Just as each bone in a skeleton has a function, so does each branch and level of the organizational chart. The various departments and job roles that make up an organizational structure are part of the plan to ensure the organization performs its vital tasks and goals.

Purpose

Organizational structures help everyone know who does what. To have an efficient and properly functioning business, you need to know that there are people to handle each kind of task. At the same time, you want to make sure that people aren’t running up against each other. Creating a structure with clearly defined roles, functions, scopes of authority and systems help make sure your people are working together to accomplish everything the business must do.

Function

To create a good structure, your business has to take inventory of its functions. You have to identify the tasks to be accomplished. From these, you can map out functions. Usually, you translate these functions into departments. For example, you have to receive and collect money from clients, pay bills and vendors, and account for your revenues and expenditures. These tasks are all financial and are usually organized into a finance or accounting department. Selling your products, advertising, and participating in industry trade shows are tasks that you can group under the umbrella of a marketing department. With differing ways to organize the tasks, you can always choose something less traditional. But in all cases, organizational structure brings order to the list of tasks.

Considerations

Employees do best when they know who to report to and who is responsible. Organizational structure creates and makes known hierarchies. This can include the chain of command within an organization. A good organizational chart will illustrate how many vice presidents report to a president or CEO and in turn, how many directors report to a vice president and how many employees report to a director. In this way, everyone knows who has say over what and where they are in the scope of decision-making and responsibility. Hierarchy can also include macro-level management. For example, one department may comprise several teams. Perhaps several departments form one division of a company, and that division has a vice president who oversees all the departments and teams within it.

Features

Organizational structure encompasses all the roles and types of jobs within an organization. A complete organizational chart will show each type of position and how many of these there are at present. When smaller organizations look at their organizational structures, they usually focus more on job roles than hierarchy. Small businesses, particularly growing ones, often change quickly — adding positions and shifting people’s responsibilities as they remain flexible enough to adapt as to go along. For these businesses, having known definitions of people’s roles can be useful, especially as things change.

Types

Organizations that are very hierarchical are usually referred to as having vertical organizational structures. Typically, these organizations want their employees having more limited scopes and performing their jobs in particular ways with little variation. Therefore, they have many layers of management to oversee that things are done correctly and uniformly. The banking industry is a good example. Money must be handled carefully and responsibility, there is significant risk involved, and rules and regulations dictate specific procedures. Small businesses, innovation-based companies and professional organizations tend to use horizontal structures. These involve fewer layers of management and more focus on peers and equality. The idea is that each person takes on more responsibility and has more freedom to perform her work as she sees fit. Group medical practices are a good example. Physicians don’t oversee physicians. There may be a managing partner who oversees the general operation, but otherwise, professionals are peers each practicing in their style — all contributing to the organization’s success.

The Importance of Organizational Structure

Small companies usually use one of two types of organizational structure: Functional and product. Functional areas such as marketing and engineering report to the president or CEO in a functional organizational structure. Product structures are used when a company sells numerous products or brands. It is important for companies to find the organizational structure that best fits their needs.

Function

Organizational structure is particularly important for decision making. Most companies either have a tall or flat organizational structure. Small companies usually use a flat organizational structure. For example, a manager can report directly to the president instead of a director, and her assistants are only two levels below the president. Flat structures enable small companies to make quicker decisions, as they are often growing rapidly with new products and need this flexibility. The Business Plan, an online reference website, says small companies should not even worry about organizational structure, unless they have at least 15 employees. The reason is that employees in extremely small organizations have numerous responsibilities, some of which can include multiple functions. For example, a product manager also might be responsible for marketing research and advertising. Large organizations often have many tiers or echelons of management. As a smaller organization grows, it can decide to add more management levels. Roles become more defined. Therefore, it is important to know which people oversee certain functions.

Communication

The importance of organizational structure is particularly crucial for communication. Organizational structure enables the distribution of authority. When a person starts a job, he knows from day one to whom he will report. Most companies funnel their communication through department leaders. For example, marketing employees will discuss various issues with their director. The director, in turn, will discuss these issues with the vice president or upper management.

Evaluating Employee Performance

Organizational structure is important for evaluating employee performance. The linear structure of functional and product organizational structures allow supervisors to better evaluate the work of their subordinates. Supervisors can evaluate the skills employees demonstrate, how they get along with other workers, and the timeliness in which they complete their work. Consequently, supervisors can more readily complete semiannual or annual performance appraisals, which are usually mandatory in most companies.

Achieving Goals

Organizational structure is particularly important in achieving goals and results. Organizational structure allows for the chain of command. Department leaders are in charge of delegating tasks and projects to subordinates so the department can meet project deadlines. In essence, organizational structure fosters teamwork, where everyone in the department works toward a common goal.

Prevention/Solution

Organizational structure enables companies to better manage change in the marketplace, including consumer needs, government regulation and new technology. Department heads and managers can meet, outline various problem areas, and come up with a solution as a group. Change can be expected in any industry. Company leaders always should strive to find the best organizational structure to meet those changes.